Challenge: Finding Better Ways to Manage Malaria in Children

In Burundi, malaria accounted for 75% of all cases seen at the health centers in 2009 and remains one of the main causes of death for children under five. As part of the strategy to scale up effective and timely case management using artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACT), and as a way to ensure early detection and correct management of malaria in children under five, the Ministry of Health (MOH) in Burundi started to pilot community-based case management (CCM) of malaria in three of the country’s 45 districts. Community case management is a strategy intended to increase access to diagnostic and treatment services for children under five years through access to appropriately trained, supervised, and equipped community health workers (CHWs) based in local villages.

SIAPS Activities: Getting Earlier Diagnosis and Treatment at the Community Level

Working in partnership with the leadership at the MOH and the National Malaria Control Program (NMCP), SIAPS helped develop protocols and job aids for CHWs to guide them in the key steps of case management, and supported initial and refresher trainings for over 520 community health workers from the two districts. To ensure that health facilities also had sufficient capacity to provide effective support to the CHWs, SIAPS conducted additional trainings with health facility and district-level staff to create a network of support for the CCM pilot. SIAPS also helped establish a mechanism to collect and use data coming out of the pilot by building the data collection and analysis capacity of CHWs and health facility staff, and by developing a database at the district level to aggregate data from each health center. Additionally, SIAPS ensured the CHWs had the necessary equipment to provide effective CCM, including mobile telephones, bicycles, commodities boxes, gloves, cups, and spoons.

The MOH, recognizing the large and growing body of evidence demonstrating that integrated CCM (iCCM) of malaria, diarrhea, and pneumonia can increase access to timely treatment and improve health outcomes, decided to evaluate the CCM pilot program for malaria to help inform the potential implementation of iCCM.

Results: CHWs follow treatment protocols but need effective supervision

Data from the 11 months of the CCM pilot indicate that CHWs in three districts saw 62,746 children under five, 59% of whom had a positive rapid diagnostic test (RDT) for malaria. Of those with a positive RDT, 82% were seen by a community health worker within 24 hours of the onset of fever. Notably, CHWs identified a higher number of cases in areas that were further from the health center compared to areas that were within 30 minutes from the health center which has clear programmatic implications for the future placement of CHWs.

CHWs identified signs of severe illness or danger signs indicating the need for a referral in about 2.5% of the children who came for consultation, and referred 43% to the health facility for further follow-up; any child with a negative RDT result should be referred, as CHWs in Burundi were not trained to treat conditions other than malaria at the time.

Correct case management includes checking for danger signs (convulsions, dehydration, etc.), diagnosis using RDTs, treatment, and counseling. Only 15% of CHWs in the pilot could recite all five danger signs. Of those, only 20% actually checked for all signs when managing a child under five with fever. According to the CCM algorithm, CHWs should also ask caregivers questions about the history of the illness episodes, such as the presence of fever and other symptoms, age, and consumption of other medicines. The evaluation showed that 60% of CHWs asked all of these questions, and 80% evaluated the presence of fever manually.

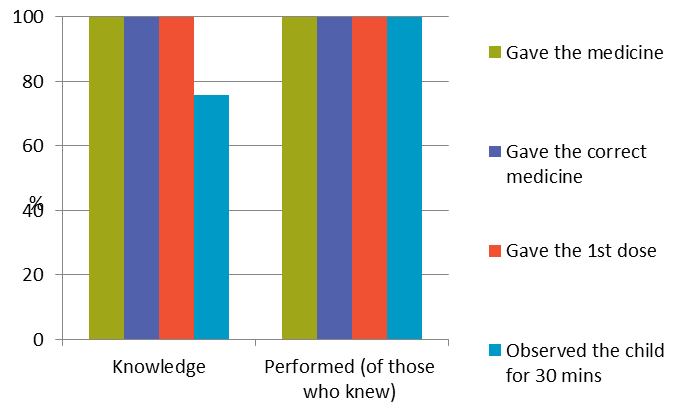

Almost all children (97%) seen by the CHWs were given a rapid diagnostic test (RDT), and over half were diagnosed with malaria. Of those diagnosed with malaria, 92% were given the correct dose of artesunate/amodiaquine (AS/AQ) within 24 hours (Figure 1). Although most CHWs could not correctly identify the 14 steps necessary to perform the RDT, of the CHWs who knew all steps for RDTs, 87%practiced them all. These results show that the biggest barrier is knowledge and its lack of translation into practice which are elements that must be reinforced in future CCM efforts.

CHWs were not adequately supervised despite the majority of CHWs stating they had received at least one supervisory visitor from the health center during the preceding three months. The major issue appeared to be the lack of available supervisory staff at the health center. Additionally, the monthly meetings with the CHWs at the health centers are not fully utilized as a complementary supervisory activity.

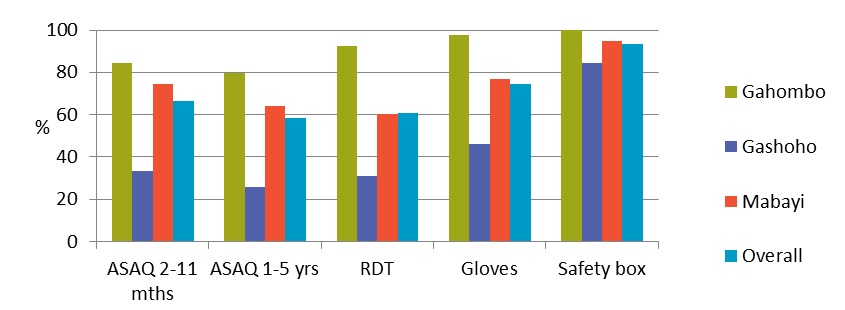

Eighty percent of CHWs had all necessary products available on the day of evaluation, although only 54% of the health centers had all products available on the day of the evaluation, as indicated by Figure 2. The majority of CHWs went to the health center to restock when they needed products, rather than complying with the monthly requisition system put in place as part of the pilot phase.

The evaluation team also assessed the cost of the pilot, and projected the costs of scaling up iCCM. While the costs of the pilot were calculated to be $394 per CHW in 2013, the cost for iCCM is calculated to be $528 per CHW in 2014. The total cost of the program for 2014 was estimated to be $1,121,952. The gap in funding of the iCCM package is estimated at 54% of the total cost for 2014 and 78% of the projected total cost in 2018 based primarily on estimated government subsidization of salary costs relating to supervision and management.

While the CCM malaria pilot program provided timely diagnosis and treatment for a large number of children under five with fever, there are areas for improvement particularly in the quality of care (primarily knowledge gaps) and supply chain management to support a CCM strategy. For iCCM to be effective, the supervision strategy should be strengthened and opportunities for continuous education—for example through monthly meetings—need to be explored. The functioning of the supply chain at the health center level also needs to be strengthened to allow the CHWs to carry out their supply chain tasks.

Next Steps: Planning for expansion

The MOH is using the results of the evaluation to mobilize resources for the expansion of iCCM and to shape the design of the iCCM model. As a result of the evaluation, SIAPS supported the NMCP and the two districts in supervising the monthly coordination meetings at the health centers. These meetings not only enable CHWs to restock their CCM supplies, but also serve as an opportunity to provide ongoing training and supervision.

References

- Plan National de Development Sanitaire 2011-2015

- Evaluation of community case management of malaria in the pilot health districts of Gahombo, Gashoho, and Mabayi, Burundi 2014